This story originally published online at N.C. Policy Watch.

A U.S. Supreme Court ruling last month struck down a federal moratorium on evictions, threatening to displace thousands of North Carolina’s K-12 students whose families can no longer pay their rents.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) temporary moratorium for areas in which there is “substantial” and “high” transmission of COVID-19 was supposed to expire on October 3. It ended August 26, however, after the Court’s 5-4 decision.

Now, educators, school social workers, and McKinney-Vento liaisons, who oversee districts’ homeless education programs, are bracing for what some predict will be an explosion of students experiencing homelessness.

Amy White, a State Board of Education member, raised the concern at the board’s meeting this month.

“I can tell you that number [families experiencing homelessness] is getting ready to explode,” White said. “I have first-hand data that suggest that there are families [who owe] six, seven, eight thousand dollars on rent.”

North Carolina’s evictions moratorium ended July 1 after Republican members of the Council of State rejected a one-month extension to align it with the federal moratorium. One notable Republican official voting against the extension: state schools Superintendent Catherine Truitt.

Feeling the impact

New Hanover County schools are already feeling the impact of the Court’s decision to end federal protections against evictions, said Rebecca McSwain, a school social worker, and the school district’s McKinney-Vento liaison.

The district has identified more than 700 students experiencing homelessness after only a few weeks of the new school year. Roughly 500 are students from last year, but at least 230 of them are new. A lack of affordable housing in the county contributes to homelessness, McSwain said.

“In a typical year, we normally identify about 60 [new students] at this point [in the school year],” McSwain said.

The district identified a total of 914 students experiencing homelessness last year.

McSwain thinks that number could double before this academic year ends.

“If I had to guess, I’d say close to 2,000,” McSwain told Policy Watch when asked how many students might be identified during the 2021-22 school year. “We’re just hoping hurricane season passes us up.”

The number of families experiencing homelessness usually increases in the coastal county after a hurricane strikes, McSwain said.

After Hurricane Florence meandered through North Carolina in 2018 causing significant wind damage and flooding, the number of students experiencing homelessness in the district jumped from about 700 to 1,500.

McSwain, however, said that experience gave her some confidence in the district’s ability to cope with rising homelessness numbers. “We found out with that, that we do know what to do,” she said. “Our social workers and other support staff are prepared to handle that many [1,500 students] or more.”

Federal funding to help

Heading into the new school year, the school district will have more resources at its disposal to assist students experiencing homelessness than it did after Hurricane Florence and at the start of the pandemic.

For one thing, McSwain said, each of the district’s 44 schools is now assigned a social worker, thanks to an influx of federal dollars. School social workers, nurses and psychologists have become a priority in most districts since the onset of the pandemic.

“We were given additional positions, so we decided to make sure each school has a school social worker because we knew we were going to need to support more homeless families and we knew the evictions moratorium was coming to an end, so we’re prepared,” McSwain said.

Most (77) of the state’s 115 traditional public school districts will benefit from additional federal dollars this school year to help families experiencing homelessness that qualify for services under the McKinney-Vento Act.

Families experiencing homelessness are covered under federal law that ensures the right of students to attend school even when they are experiencing homelessness or don’t have a permanent address. The law’s intent is to reduce barriers that prevent homeless youth from enrolling, attending and succeeding in school. Those barriers include residency requirements and a lack of transportation and documentation, such as birth certificates and medical records.

North Carolina received $23.6 million in American Rescue Plan Act-Homeless Children and Youth relief funds to address the “urgent needs that have evolved from the pandemic.” Districts may use the money to address the social, emotional and mental health needs of students, trauma-informed care training for staff and to hire staff for local homeless education programs at the district and state level.

Charter schools, lab schools, virtual schools and the Innovative School District will also benefit from the supplemental federal funding.

The state’s regular McKinney-Vento allotment from the U.S. Department of Education for the 2021-22 school year is $3.9 million. Districts awarded the three-year grants will receive double their allocations under a spending plan approved by the State Board of Education.

Despite the boosts in funding, officials remain concerned about a rapid rise in homelessness and the accompanying challenges it will bring.

“One of the biggest challenges we all face is the moratorium being lifted,” said Lisa Phillips, the state coordinator for the N.C. Department of Public Instruction’s Homeless Education Program. “So, many of our families will be displaced again, and there is the uncertainty of what is going to happen with another [COVID-19] variant and others being identified and the uncertainty of what might happen with physical placement.”

Phillips said McKinney-Vento families also face food insecurity and the rising cost of basic needs due to the pandemic.

“I think our transportation divisions, our education administrators, school officials and other support agencies are all coming together to ensure that, as we move forward, that we have that communication with our families, we have ways to ensure that their children are receiving child nutrition services and if there is a need for additional food where that might be located in the community,” Phillip said.

Identifying students

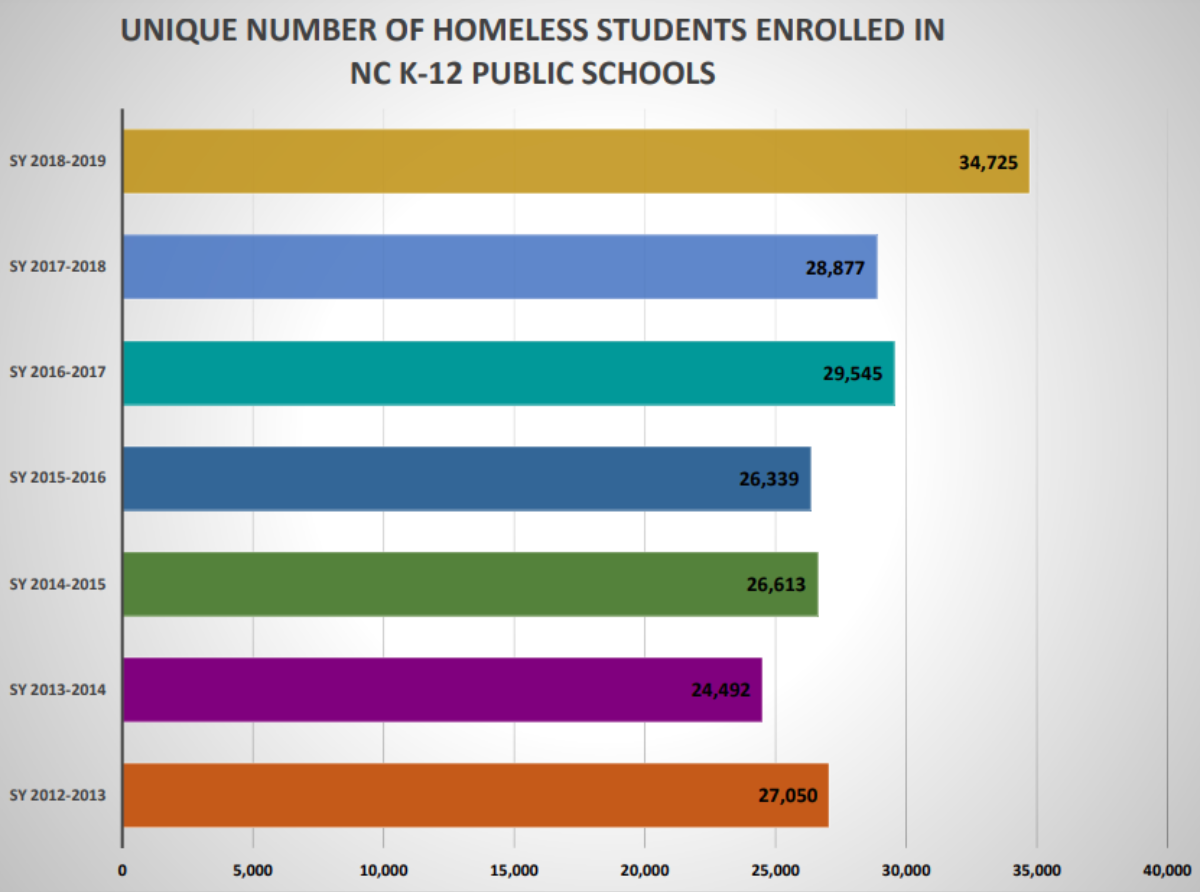

During the 2018-19 school year, North Carolina school districts identified 34,725 students experiencing homelessness. The number was much higher than in previous years because Hurricane Floyd hit North Carolina, forcing many school districts to close. When students are not in school, state education officials say that it’s more difficult to identify whether they are eligible for McKinney-Vento services.

Not long after the pandemic closed schools to in-person instruction in March 2020, school districts identified about 28,000 students experiencing homelessness.

Last year, when most students learned remotely, school districts could only identify 23,764 such children.

Districts expect to identify more students with a return to classrooms full-time for in-person instruction this school year.

“The hard part in all of this is, as school has started back, we are flooded with an influx of students that are carrying and presenting themselves as homeless,” Phillips told the SBE. “The homeless liaisons are overwhelmed at this time.”

Cumberland County situation is typical

Pamela Story, the school social work coordinator for Cumberland County Schools (CCS) and the NC Homeless Liaison of the Year, was on the move early Monday morning.

A family of eight from New York displaced by Hurricane Ida appeared at a CCS middle school to enroll several children in district schools. The family is living with relatives but qualifies for McKinney-Vento services.

Story made her way to the middle school to assist a new support staff member in enrolling the students in the middle school, an elementary school and a high school.

“They’re considered homeless because they’re coming to stay with relatives and they have lost their permanent, fixed and adequate residence to bunk up with their aunt and uncle,” Story said. “It’s a temporary situation but they do qualify to receive all the services they need while they try to pull the pieces back together.”

Students identified as experiencing homelessness often have a roof over their heads, but their situations are frequently tenuous and far from adequate. The McKinney-Vento definition of homelessness includes families sharing homes due to a loss of housing or economic hardship, as well as those living in shelters, motels, trailer parks, automobiles, parks, or even under bridges.

CCS identifies between 600 and 800 students experiencing homelessness each year. It only identified 405 last year when the students mostly learned remotely.

“They were just disengaged,” Story said, referring to students. “Outreach is our strength, and we reached out as much as we could. We went to hotels and motels and we did everything that we could [to identify students for McKinney-Vento services].”

Like New Hanover Schools, CCS expects to identify more students experiencing homelessness this year due to the Court’s decision to lift the evictions moratorium, Story said.

A dearth of affordable housing in Cumberland County also contributes to homelessness, she said.

“We just had a consultant come to Cumberland County who told us what we already know; the reason we have the number of homeless families that we have is because of the lack of affordable housing,” Story said.

Story is excited about having additional federal funding to assist families experiencing homelessness. She plans to use some of the money to hire additional staff assigned solely to assist homeless families. Often, homeless liaisons have multiple responsibilities.

“Because you have to have a homeless liaison in every school district, I feel that position should be a permanent position in every district that is funded by the state,” Story said. “But because it isn’t, my plan is to use some of that money to bring on additional staff whose job will be to help look for students, help students stay in school and work to improve attendance.”

Support independent local journalism. Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle.

Comment on this story at backtalk@indyweek.com.