The Durham City Council election of 1979 was a doozy, sweeping a conservative slate of seven white men into office. I was on the other side of that election, working for the losing ticket and then watching helplessly as the new council majority voted at its first meeting to ram a highwaytoday called the Durham Freewaythrough the close-knit African-American neighborhood of Crest Street.

Later that month, I sat down at my new Olivetti typewriter to bap out a memo to a few of my friends. I called it “Newspaper Thoughts,” lamenting the power of the local media to beat us in our fight to stop the highway and to elect a racially diverse slate of council candidates. I filled the memo with grandiose notions of publishing a paper to rival the dailies, a paper to be filled with coverage of church suppers and the Civitan Club that would draw members of the “white working class” into our bi-racial electoral coalition. A few friends kicked “Newspaper Thoughts” around for a while and then kicked it into a corner.

A year later the newspaper idea re-emerged when Dave Birkhead and I were among 17 people who got arrested while sitting in at the corporate headquarters of Carolina Power & Light Company. We were there to protest the construction of the Shearon Harris nuclear plant in the wake of the meltdown at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania.

We protesters held romantic notions of our own importance. After our arrests, we dubbed ourselves the “Raleigh 17,” and we didn’t like the way the local newspapers labeled, discounted and ignored us. As Dave and I rode from Durham to Raleigh to be tried for our act of civil disobedience, we ranted about the media for a while and then I said, “Let’s start a newspaper of our own.” And he said yes.

As it turned out, I had some time to think about it. That day the judge sentenced me to eight days in the Wake County jail.

Time passed, but our newspaper dream lived on. I finished my Ph.D. in education at Duke. Dave kept his typesetting business going and became a father. We visited publications we admired around the country, including the Voice in Flint, Mich., where I spent four days hanging out with its frenetic burger-guzzling publisher, a guy named Michael Moore who wasn’t yet interested in making films.

Then, on June 1, 1982, Dave and I pulled the junk out of a windowless cinderblock room on Hillsborough Road in Durham. We hauled in a battered metal desk, which we had bought for $35 from the Durham County jail, and I sat down behind the desk to start a newspaper.

That day I slapped up a handwritten sign on the wall: “No Guts, No Glory.”

Thirty years later, I have decided to sell the Independent. Why now? It’s simple. At age 61, I can see so much that is new and exciting and different ahead of me. I’m on the Durham City Council myself nowhow did I get to be one of the old white guys?and I enjoy the work immensely. As for the Indy, I’m simply ready to lay this glorious burden down.

Publishing the Independent has never been easy. On the very first day on Hillsborough Road, I wrote a letter to two liberal philanthropists from New York that I had never met, and a week later they sent me a check for $2,000. That was our seed capital. Dave and I recruited a 27-year-old journalist from the Greensboro Daily News, brave, driven Katherine Fulton, to leave her job and become the editor of a paper that didn’t yet exist. Somehow, we dragged this little newspaper into life out of the dust of that cinderblock room where the marijuana smoke leaked through from the car stereo shop on the other side of the wall.

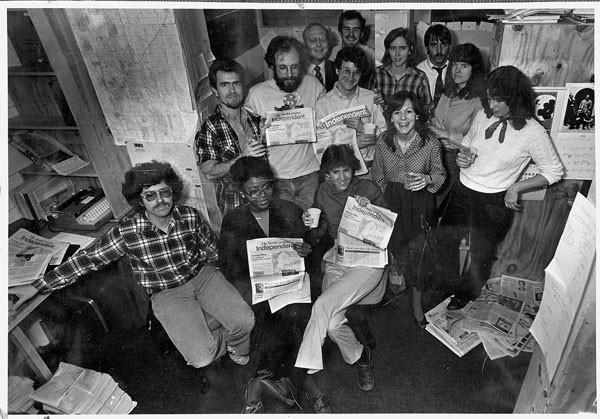

We didn’t own any newspaper racks; we simply threw 10,000 copies of our first issues on the floor beneath the racks of other publications. We didn’t have a delivery crew; for the first couple of years, everybodyreporters and ad reps alikehad a delivery route to run each week. On our first day of publication, we had a staff of seven. Everybody made the same pay$10,000 per year until our money ran low and we cut that pay to $8,000except for Dave, Katherine and me, who got barely any pay at all.

We had crazy high goals. We wanted to bring down Jesse Helms and big tobacco and end the death penalty in North Carolina. That was our idea of a worthy mission and a helluva good time, and we went about it with a vengeance. Many times we worked 40-hour weeks before Wednesday morning came around. I wrote stories and columns, helped with editing and paste-up, delivered the paper, made sales calls and kept the books by hand on those long green ledger sheets. Today somebody would probably call us social entrepreneurs, but we thought of ourselves in those early years as only accidentally in business. We were activists and journalists out to change the worldor at least bring justice to our beloved North Carolina home.

We made every possible mistake, and I’m still too embarrassed to list them here. In the meantime, we raised money in $5,000 and $10,000 chunks from a group of shareholders who provided the capital we needed to sustain our losses during that first difficult decade. Our shareholders knew they’d probably never get their money back. That was part of every understanding despite our relentless pursuit of elusive profitability. What we offered our shareholders was something else, something they wanted more. As we wrote in one prospectus, “We ask you to join us in taking a stand, in one small place, for nothing less than the soul of a generation, the moral purpose of journalism and the future of the South.”

Sixty-one shareholders joined our cause, and first among them were my parents, Elliot and Rosel Schewel, who raised me up in Lynchburg, Va., loved me everlastingly, sent me to Duke and kept putting money into the Independent way past the time when any rational investors would have stopped. For the first time in 30 years I’m saying it in print: Thanks, Mama and Daddy, for this and everything.

Along with the hardship came many triumphs, large and small. Early on, the Columbia Journalism Review praised our “inviting Southern feel” and our “spine of steel.” Candidates began to covet our election endorsements, which have provided the crucial margin of victory in scores of local and statewide elections over the years. Stung by our investigation of his department, then-North Carolina Secretary of Transportation Tommy Harrelson called us “left-wing attack media from hell.” His words pleased us greatly, so we put them on a T-shirt.

All this work won us awards, a slew of them, almost every national journalism award except the Pulitzer, doggone it. I always wanted one of those thingsand that brings me to the new owners of the Indy. Richard Meeker and Mark Zusman, the partners in the new North Carolina company that is buying the Independent, already have a Pulitzer under their belt. Richard and Mark’s newspaper in Portland, Ore., Willamette Week, is the only alt-weekly in the country to have won the best Pulitzer of all, the award for investigative reporting.

I have been friends with Richard and Mark for many years, first meeting them long ago at conventions of the nation’s alternative newsweeklies. Richard Meeker is the brother of former Raleigh Mayor Charles Meeker, and their father lives in North Carolina as well. On many of Richard’s visits to his family, he and I have gotten together to talk about the newspaper business. Several months ago, over a cup of coffee at the Raleigh Times, Richard wondered if I’d be interested in selling the paper to them. I said yes. I had no intention of shopping the paper around. I knew these were the right buyers, and I knew the time had come.

I am happy that this is the best possible landing place I can think of for the future of the Independent and indyweek.com. While Richard and Mark know how to run a profitable company, their mission is to produce great journalism for their readers. They do just that in their two other papers in Portland and Santa Fe, N.M., and I believe they will keep the Independent‘s legacy intact.

This started with their first decisions. Lisa Sorg will continue to edit the paper with fire and wit. The superb Gloria Mock will retain the critical role she has played in advertising and marketing for the past 19 years. And the new owners are elevating our splendid general manager, 16-year Indy veteran Susan Harper, to the publisher’s job.

Three years ago the Indy launched the Hopscotch Music Festival in Raleigh, whose re-creation each year is the most fun I’ve had in a long time. In fact, Hopscotch is not part of the sale to the new owners of the Independent. Although Hopscotch and the Indy will continue a close relationship, I will continue to be president of the company that owns and runs Hopscotch.

As with any transition of this magnitude, there are hardships, too. Four people, my wonderful co-workers, will lose their jobs, to be replaced by others. One of those people is Sioux Watson, who came to the Indy as our first ad rep two months after we began publishing in 1983. Sioux rose to the position of advertising director, and when I stepped away from day-to-day operations at the Indy in 1999, she became our publisher. For 29 years, Sioux has been the steady hand, caretaker, crisis manager and cruise director. She has been our company’s public face, winning friends for the Indy everywhere she goes. And for those 29 years, she has been my close friend and colleague.

So it ends. I was 32 years old when we published the first issue of the Independent. I look back now in surprise to find that it became my life’s work. As for Jesse Helms, we never did defeat that son of a gun. Big tobacco still thrives worldwide, but not in North Carolina. The death penalty is still with us, but our state has not executed anyone in five years and opposition to this barbaric practice continues to grow.

We’ve published thousands of writers, photographers and illustrators; put millions of papers on the street; attracted tens of thousands of people to our rich and compelling website; helped create and support the Triangle’s art scene and music boom; honored dozens of people with our Citizen Awards and Indies Arts Awards. We’ve fought to keep poetry alive and great investigative journalism thriving and we’ve made all the right people mad. Standing at the polls on Election Day, I watch people pouring in with the Independent‘s voting recommendation clutched tightly, and I am proud.

There are so many of us to share this pride, especially the fabulous staff members of the Independent who have each made their own special contribution. There are our dedicated freelance writers and the readers we serve and the advertisers who keep us alive and sustain us. There are our shareholders, and among them the few who have made the mission of the Independent their own passionate cause as board members and advisorsAdam Abram, Marty Belin, Trip Van Noppen, Jenny Warburg and Elizabeth Woodman. Above all, there is my beloved, Lao Rubert, who still wants me to pursue every ambition and every dream, whose commitment to her own work for the most vulnerable members of our society still amazes me after 38 years together, and who loves our two grown boys as ferociously as I do.

Here is the mission of the Independent, which we adopted long ago:

To publish the nation’s best alternative journalism;

To help build a just community in the Triangle;

To create a great workplace for every individual here; and

To make a profit doing it.

It is true that we missed that final goal during most of the past 30 years. But the folks who have worked at the Indy never did it for the money. They worked here because they cared about our community and about one other, because they believed in the mission and found that they could continue to create the Indy anew for themselves year after year. It is noble work, and I trust that together we have been of some service.

Carolina Independent Publications shareholders

Below are the shareholders who have owned and supported the Independent over the past three decades. Steve Schewel and his family own the majority of the shares in the company, which is selling the paper on Sept. 27 to ZM Indy, Inc.

Adam Abram

Mary and Elias Abu-Saba

Hope Aldrich

Marty Belin

Emily Bingham

David Birkhead

Ed Bloomberg

Patty Blum and Harry Chotiner

Alicia Blum-Ross

Sally Cardamone

Gerry and Pamela Farmer Cohen

Hank Cole

Sally Fishburn Crockett

Kenny Dalsheimer and MaryBeth Dugan

Wells Eddleman

Lois Feinblatt

Carol and Ping Ferry (deceased)

Robert Fishburn (deceased)

Emily Preyer Fountain

Alice Franklin

George Fulton (deceased)

Katherine Fulton

Robin Hanes

Harry H. Harkins

Alice Hoffberger

Paul Holmbeck

Karen Love Jessee

Lisa Klopfer

Joe Pfister and Jenny Knoop

Bill Knox

Tommy and Anna Lawson

Steve Lerner

Bill Matthews

Rick Melcher

Nancy Milio

Mary Mountcastle and Jim Overton

Ken and Katharine Mountcastle

Grace Nordhoff

Nancy Nordhoff

Todd Oppenheimer

Stanley Overton (deceased)

Jane Preyer

Richardson Preyer (deceased)

Lee Richardson (deceased) and Val Blettner

Jean Riesman

Hildegard Ryals

Susan Lupton and Bob Schall

Michael Schewel

Rosel and Elliot Schewel

Steve Schewel

Susan Schewel

Jane Sharp-Macrae

Jane and Adam Stein

Phil Stern (deceased)

Katherine Stern Weaver

Jeanette Stokes

Jennifer McGovern and Steve Unruhe

Rivka Gordon and Tripp Van Noppen

Jenny Warburg

Jim and Claudia Warburg

Elizabeth Woodman