Dabney Hall, which houses N.C. State’s chemistry department. Photo: N.C. State University.

This story originally published online at N.C. Policy Watch.

On the morning of October 7, N.C. State University chemistry professor Jim Martin arrived at Dabney Hall carrying boxes to pack up his office in Room 822A. In less than 10 minutes, an air sensor gave him some disturbing results.

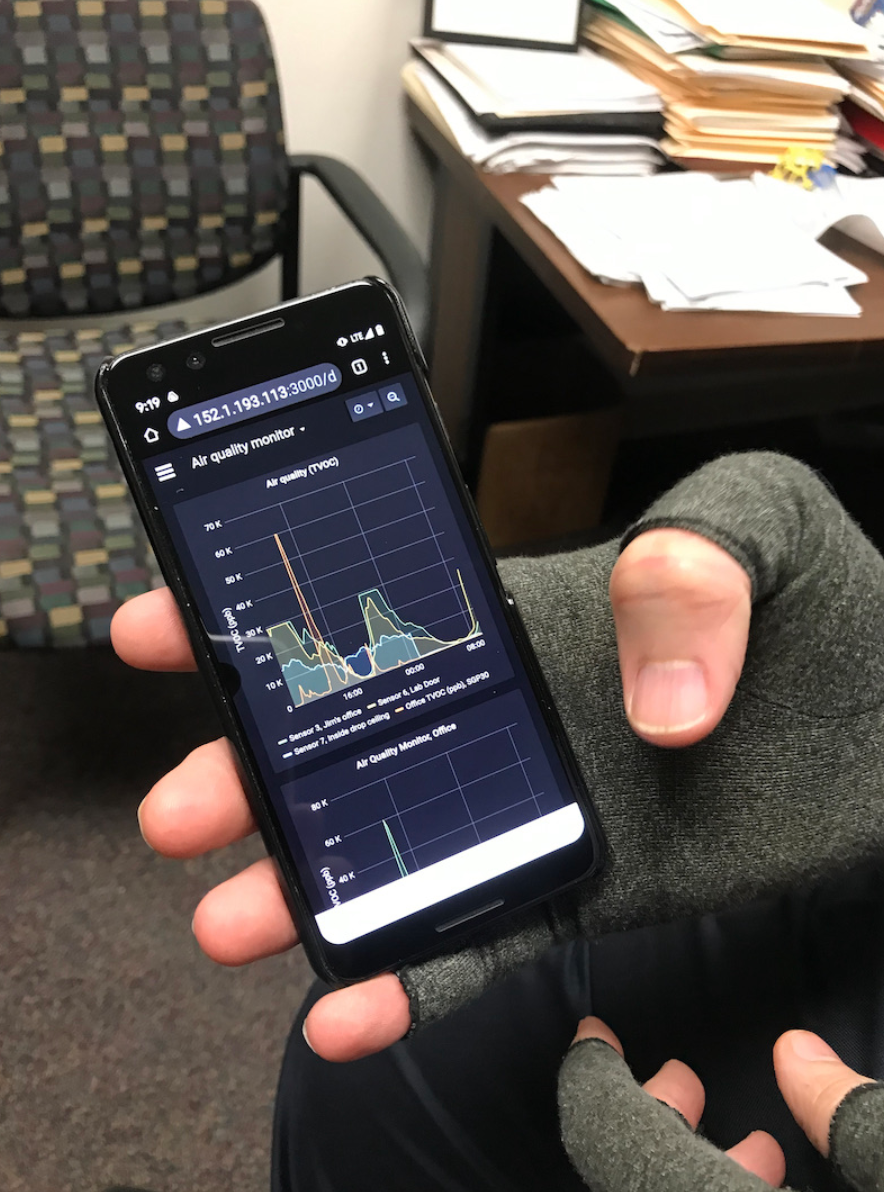

The air sensor graph shows the levels of total volatile organic compounds at various locations on the eighth floor of Dabney Hall. This photo was taken in Professor Jim Martin’s office. The sensor showed the presence of VOCs even though he does not use chemicals in his office. (Photo: Lisa Sorg)

The sensor, which he had installed on top of a filing cabinet, sends data to a web server that Martin can access on his smart phone. The graph showed spikes in levels of potential harmful chemicals known as volatile organic compounds, over the past week. Although the sensor provides only approximate values and relative changes over time, Martin’s office contains just books and paper.

“This should be essentially zero,” Martin said, as the sensor climbed. “But this tells me that’s not so.”

Dabney Hall, which houses the Chemistry Department, has a long history of ventilation problems. Those problems could be exposing students, faculty members, and staff to at least a dozen harmful compounds, including benzene, a known carcinogen, according to air tests conducted by the university’s Environmental Health & Safety Department in December 2019.

But despite a years-long campaign by graduate students, faculty members and a Chemistry Department safety official, the university has been slow to address the problem or even conduct comprehensive air sampling.

Volatile organic compounds are typically industrial solvents, as well as components in paint thinners, hydraulic fluids, adhesives, and more, according to the EPA. Exposure to these compounds, also known as VOCs, can irritate the eyes, nose and throat; cause nausea and vomiting, and, depending on the length and intensity of the exposure, can cause cancer and damage the liver, kidney, and nervous system.

Melinda Box, organic chemistry lab supervisor and safety officer, detailed the air quality problems at Dabney Hall in an official complaint filed October 17. The complaint, the second Box has filed, expresses frustration at the lack of support from the Chemistry Department and the university. Those working in the building’s labs have repeatedly called for department officials to do proper air sampling and to fix an old and poorly functioning HVAC system.

“My overarching concern is that this pattern of delaying and undermining meaningful air sampling will continue,” Box wrote in her complaint. “.. The earliest expectation I have been given for moving anyone out of Dabney Hall is five years. I am concerned that this is an unconscionable length of time to leave the occupants in a compromised situation and in ignorance of the extent of that.”

Martin said that since 2019 several graduate students have reported feeling ill with headaches, nausea, and occasional vomiting while working in the lab. The students contacted university Environmental Health & Safety officials.

An air sensor in Professor Jim Martin’s office, Room 822A of Dabney Hall, the chemistry building. It sends data to a server accessed by Martin’s phone. (Photo: Lisa Sorg)

The response? “Radio silence,” Martin said.

Ken Kretchman, director of Environmental Health & Safety, told Policy Watch that the chemistry students, staff and faculty have “bad information” based on faulty analytical methods. Kretchman told Policy Watch that his department’s own air sampling, which he said adheres to the EPA standard for industrial workplaces, has found no concerning levels of VOCs, with all of them registering well below the recommended exposure limit.

The people complaining, Kretchman said, represent a small percentage of those who work in the department.

Box, however, told Policy Watch that because they fear professional retribution, “only a small minority of people feel secure to speak up.”

Nonetheless, Kretchman said, he helped arrange for graduate students to work in a different lab. Renovation has begun on the eighth floor of Dabney Hall, where there have been the most concerns. “We’re taking action even though there isn’t any demonstrated over-exposure, which is actually based on my recommendations,” Kretchman said. “So the Dabney people aren’t being mistreated.”

“I wouldn’t try to be a chemist,” Kretchman went on. “They aren’t occupational health professionals. I don’t know how to say it any clearer than that.”

Box’s job is to ensure the safety protocols are followed in the chemistry labs. She said OSHA standards are “severely outdated.” A 2016 article in Industry Safety & Hygiene News supports Box’s argument, stating that some legal exposure limits are based on science from the 1960s.

In 2014, David Michaels, assistant Secretary of Labor for OSHA, made a public speech acknowledging the dearth of meaningful regulation. “While many of these chemicals are known or suspected of being harmful, only a small number are regulated in the workplace,” he said. “New chemicals are being introduced into worksites every year, and we are struggling to keep pace with the potential hazards. As a result, forty years after the creation of OSHA, thousands of American workers are still becoming ill and dying from exposure to hazardous chemicals.”

Several graduate students and faculty members, as well as Box, said Kretchman has been dismissive and defensive throughout their dealings with him. Nor are Kretchman or other top Chemistry Department officials considering the potential cumulative effects of multiple compounds in the air—at least a dozen, according to a sampling conducted by EH&S.

Martin said Kretchman’s department didn’t respond to concerns until after several graduate students contacted the university fire marshal. “And then, the response has been incredibly delayed,” Martin said.

“This is not an easy problem to solve,” Martin said. And nobody says that it is. I’m not calling for the building to be shut down. I’m calling for it to be fixed.”

“Potentially grave health consequences”

Across the hall, Martin entered his science lab, where no one was working. He had placed air sensors near both doors to better understand if compounds were entering the lab, which does not handle VOCs, from the hallway. A possible source of the contamination is the “cross-talk” in the ventilation systems, he said, from labs where chemicals are handled and stored, through ductwork into hallways and offices.

Dabney Hall was built in 1969, and many of the building’s labs are outdated. There could be many factors contributing to the poor air quality, Martin said. Condensate—moisture—in air ducts could absorb the compounds, and send them through the eighth floor ventilation system. “I have been raising issues about this building since I was hired,” said Martin, who began working at N.C. State in 1994.

In fact, the university had been aware of the failures of the building’s outdated HVAC system and its potential danger to those working in Dabney Hall since at least 2016. That’s when a commissioned ventilation survey by RMF Engineering documented hazardous chemical fumes and the major problems with the building’s aged HVAC system.

The Department of Chemistry Safety Committee, which Box chairs, referenced that survey in a draft memo to the Dean of the College of Science in March of last year.

“A large number of chemicals employed for research purposes in Dabney Hall are volatile solvents and organic compounds that are well-known to be carcinogens, mutagens, or cause other harmful effects,” the committee wrote in its memo. “As such, with the current deficient ventilation system, our students, researchers, faculty, and staff daily experience unknown exposure levels that could lead to potentially grave health consequences.”

“Our urgent request is that self-closing doors with windows be funded, supplied, and installed by the end of August 2020,” the committee wrote. “And further, that the renovation and repair of the ventilation infrastructure of Dabney Hall, in part or in whole, be funded, planned, and initiated as soon as possible to minimize health impacts within current system capacity.”

Gavin Williams, at the time a full professor and associate head of the Chemistry Department, recommended that the memo be forwarded to the Dean of the College of Science. But Ed Bowden, then the head of the department, never sent it. Bowden has since retired and no longer works for the university.

Berkley Griffin, a grad student who works and teaches in the labs in Dabney Hall, said students and faculty have been accustomed to the building’s problems. Getting trapped in the frequently failing elevator is considered a rite of passage, as is finding labs covered in pollen each spring when the HVAC system dumps it—along with the usual coating of dust—all over their work spaces. But they didn’t realize how dangerous it might be.

Opening the windows in several of the labs has been considered the only safe way to work in them for years, Griffin said. “When it’s humid, it’s humid inside,” Griffin said. “When it’s cold, it’s cold inside. When it’s hot, it’s hot inside. These aren’t ideal working conditions, but it’s sort of the only safe way to do it.”

But in 2019 they began to think the problem went beyond the quirks of an old building. She and other grad students asked questions and filed complaints, which seemed to go unheeded.

“But we’re scientists,” Griffin said. “So we decided we would document it.”

Griffin and two other grad students recorded their experiences with the harsh vapors they and others encountered in the building: where they were, when they occurred, how many people were experiencing them. They contacted the Environmental Health & Safety office but got no reply.

“When we contacted them a second time, they replied but it was a brush off,” Griffin said. “It was basically just, ‘Yeah, well, you’re in a chemistry building.’”

Williams, now the interim head of the Chemistry Department, did not return multiple emails from Policy Watch requesting an interview.

The Environmental Health & Safety office didn’t take the complaints seriously, Griffin said. But OSHA did. After receiving their complaints, the federal agency visited the building in 2019. After that, Griffin said, the university’s Environmental Health & Safety office couldn’t continue to ignore them completely. But what they did wasn’t much better, she said.

EH&S used equipment called a Photoionization Detector, which is “like a smoke test apparatus” for volatile organic compounds, Griffin said.

“They said they’d leave it with us,” Griffin said. “Because again, we’re scientists, as soon as they left it with us we tested it to make sure it was sensitive enough. We did a basic calibration test and it absolutely failed the standard test. They just gave us a faulty sensor. The whole thing has been fraught with absurdity.”

“It’s a frightening culture,” Griffin went on. “You say something like, ‘We’ve been exposed to something and we’ve documented it’ and they say, ‘Well, what is the permissible limit for exposure to these substances? Are you sure there is a limit? Maybe you didn’t measure properly.’ Their first response is always to dismiss it, to try to prove they’re still following regulations, that they’re in compliance.”

The case of mysterious insulation

The department finally announced it would begin a renovation and replacement of the air system on the eighth floor—the most highly affected—this month. That’s progress, Box said, but the school hasn’t kept her, the faculty or the grad students who have pressed this issue apprised of exactly what that will look like. There needs to be proper ductwork testing, Box said, and the university should preserve material that could show what people working in the building have been breathing for years.

Late last month, Box wrote in her complaint, a facilities worker was seen pulling insulation from the supply duct for Room 824, where those volatile chemicals had been stored.

Martin said he saw the worker and the insulation as the material lay on the floor. “It was just falling apart, black and gross,” Martin said, adding that the worker told him he was unblocking heating and cooling coils.

Box said the timing was curious. “Unfortunately, that doesn’t seem as likely as the intentional removal of evidence and contributing material to the release of VOCs in offices to which that duct runs.”

Martin has since moved out of his office to a temporary on the Centennial Campus while the renovation is underway. His outspokenness has earned him a reputation, he said, “a bit of a persona non grata because of that.”

Martin is a tenured professor, a status that should insulate him from political retribution for speaking out. “I have done my darndest to try to work within the system to change. But if somebody else talks to people, and they asked me questions, and I’ll tell you what I know. I want this university to be the best that it can be.”

Support independent local journalism. Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle.

Comment on this story at backtalk@indyweek.com.