David Gordon Green is a man on the move. Right now, it’s Sundance time, which means his current home is in Park City, Utah.

“I don’t live anywhere right now,” he confesses in an interview in the atrium of the Park City Marriott. “Lately, I’ve been staying in Texas, where I have a lot of family.”

It makes sense that the 1998 graduate of North Carolina School of the Arts doesn’t have a settled address, for he is in the middle of a wild ride. A year ago, he shot All the Real Girls in Marshall, N.C., which is about a half-hour’s drive north of Asheville. After editing the film, he’s in Park City this week to promote it, before the film opens nationwide in theaters next month.

He’ll hardly have time to savor the accomplishment, however, because next fall he is slated to start production in New Orleans on an adaptation of John Kennedy Toole’s much-loved novel, A Confederacy of Dunces. The script is by Steven Soderbergh, one of Green’s idols and now a friend. With a larger budget and the possible participation of major stars, this will be a project of a greater magnitude than his first two films.

Despite his rapidly elevating profile, Green doesn’t look much like a hipster filmmaker. Instead of designer clothes and shades, he wears ratty T-shirts and zippered sweat jackets. With the heavily-loaded backpack he walks around with, Green looks more like a disheveled college student than a 27-year-old who is emerging as one of America’s more interesting and potentially important young filmmakers.

Only two years ago, Green made a loud splash on the American independent film scene with George Washington, a touching, whimsical story of a group of mostly African-American youngsters. Shot in and around Winston-Salem, the film’s gorgeous photography and heartfelt performances from an amateur cast announced Green as a major new filmmaking talent. Nonetheless, the Sundance selection committee passed over George Washington that year.

But last Sunday, about 2000 people filled a Park City high school auditorium to see what Green would offer as an encore. Following a lavish introduction by Geoffrey Gilmore, the festival’s director, who described him as a visionary artist, Green himself took the stage to hearty cheers. After a few acknowledgements, the lights went down and the film began.

All the Real Girls is a deceptively simple tale. Paul (Paul Schneider), a notorious small town Lothario, falls madly in love for the first time. There’s a small catch, however: Noel (Zooey Deschanel), the object of his affection, is the 18-year-old younger sister of his best friend, Tip, who doesn’t want Paul anywhere near his virginal sibling.

Despite its simplicity, the film manages to defy expectations. Instead of the usual teen movie plot contrivances, the film focuses on atmosphere and emotion. It’s a story of being young, passionate and utterly lost. The two central characters are undefined as adults and this lack of definition haunts their attempts to be madly in love with each other. Filled with gorgeous photography and a surprising amount of daffy humor, All the Real Girls is a movie experience quite unlike anything that’s been seen recently in theaters.

In fact, one would have to go back a couple of decades to find films that resemble the loose, free-associative storytelling of All the Real Girls. This is no accident, for Green is a huge fan of the celebrated American films of the 1970s, a time when now dormant filmmakers like Hal Ashby, Terence Malick and Dennis Hopper were pushing the narrative envelopes, and contemporary masters like Coppola, Scorsese, Spielberg and Altman were making their earliest (and to many, their best) films.

“The period from 1968 to 1980 in American films is where the influence is, the foundation of my interest in making films,” Green says. “Camerawork and editing, and acting and storytelling, that’s when they had it going on for a long time,” he continues.

It was at NCSA that Green received his movie education, thanks in large measure to the school’s vast archive of prints. “I worked in the archive and helped them organize it, Green recalls. “It turned me on to films that I never would have known about, and there were 35mm prints of films that I’d been in love with since I was a kid, but I’d only seen the edited-for-TV versions.”

After film school, he moved to Los Angeles to work for producers and studios, in order to better understand the business side of the industry. Unsurprisingly, Green was dismayed by the realities of movie production, in which profits are much more important than art, and he returned to North Carolina a wiser filmmaker. “George Washington was a reaction to a lot of my frustration with the ways movies are made,” he says.

Thanks to the critical success of George Washington, Green was able to find backing from Sony Pictures Classics for his sophomore effort. The story’s premise was an old one–Green and Schneider had been batting it around since 1997. At the time, the two graduating NCSA seniors wanted to make a movie about this crucial period of transition in their lives.

“There aren’t a lot of examples of films that capture the insecurities, the awkwardness and the magical pleasures of young relationships,” he says, citing older films such as Splendor in the Grass, The Last Picture Show and Say Anything as favorites of his that mine such territory.

Although Green admires the work of director Terence Malick (Badlands, The Thin Red Line), he often resembles Steven Spielberg in his use of children, his extensive pop literacy and his fondness for evoking nostalgia and innocence in his films. There’s a time warp quality to his work; his films seem to be set in the South, but it’s a gauzy, aestheticized world.

“I was looking for a town that had a timeless quality to it, that wasn’t full of Starbucks and Wal-Marts and all that. … Marshall was a time capsule, a town that hadn’t changed since 1959,” Green says.

This innocent desire to recreate a halcyon past that generates much of Spielberg’s artistry, seems to drive Green as well. But Spielberg also had burning, precocious ambition, a quality that Green also shares, ever since he decided to transfer from the University of Texas at Austin to the nascent film program at Winston-Salem.

At about $1 million, the new film’s budget is small by almost any standard, other than the miniscule budget of George Washington. Still, the budget was sufficient for Green to conduct an extensive audition process.

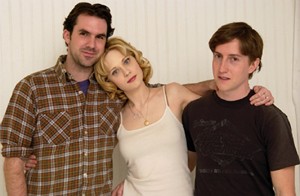

After trying out a handful of finalists opposite Schneider, Green settled on Deschanel, a talented and energetic performer who won raves last year for several small roles, most notably as Jennifer Aniston’s co-worker at the makeup counter in The Good Girl.

Green places a tremendous amount of trust in his comrades, and receives an extraordinary level of loyalty in return. When, two days into the shoot, a supporting player dropped out, Green simply turned to another pal from NCSA, Danny McBride, to play the role. McBride, a camera operator for VH-1 and other channels in Los Angeles, had never acted before, but Green had every reason to believe that his Winston-Salem buddy could pull off the film’s principal comic role.

Perhaps the greatest risk Green took was casting his close friend Schneider in the film’s lead role. The Asheville native is a virtually unknown actor, having only begun acting on a lark during film school (where his concentration was in editing) and then playing a supporting role in George Washington.

One might imagine Sony wanting a bigger name in the role, to protect their investment. However, Green points out that the $1 million budget is miniscule in the world of feature filmmaking. “I’d rather have more freedom [at that level] than have creative boundaries [as the price of a larger budget].” Besides, Green cherishes the creative potency of a volatile cast. “I really like to blend non-professional actors, unknown actors and professionals with a lot of experience. Everyone’s got something to offer, they can bring a lot to the table.”

Schneider says that any pressure he might have felt in carrying a romantic lead opposite a fairly well-known actress was swept away by the collegial atmosphere on the set. “There was no pressure attacking the character, because David and I wrote this story back in 1997,” he says. “I didn’t want to intellectualize the character–I mean, part of the movie is about NOT intellectualizing things, not being able to get out your feelings.”

“The pressure I did feel was an obligation to the things that have happened to me in real life, to David in real life,” he continues. “I want people to see this movie and say ‘you know, that happened to me,’ or ‘I’ve heard of that happening to someone else.’”

In All the Real Girls, the rapport between Schneider and Deschanel contributes to some memorable moments. One such scene, set in a bowling alley, drew laughter and applause from the Sundance premiere audience. In it, Paul and Noel embrace in an odd clinch, in the middle of a bowling lane. The scene ends with Schneider doing some spasmodic dancing, right behind Deschanel.

The scene’s blocking was a result of rehearsal experiments, and an old gag of Schneider’s.

“There was this woman I used to temp with, a large black woman. I used to stand behind her and do the ‘running man.’ She’d just look at me like I was this crazy white boy.”

McBride and Schneider are only two of Green’s friends involved with the film. Tim Orr, another NCSA classmate, served as director of photography, just as he did on George Washington. Orr, in fact, had two films at Sundance: In addition to All the Real Girls, his earthy, warmly naturalistic camerawork was seen in a rapturous film called Raising Victor Vargas.

If Green is nervous about the prospect of meeting even higher expectations and directing more famous actors, he doesn’t show it. Rather, it’s clear that he expects to develop fraternal relationships with any movie star that decides to act in one of his films. “I don’t like the idea of working with people who aren’t my friends,” he says firmly.