Exotic Meat Month

Bull City Burger and Brewery, Durham

My wife used to work for the illustrious expat food writer Patricia Wells. The last time we had lunch together, Wells asked for our thoughts on the cut of pork known in French as the cigalline, which she’d been trying to get from her butcher. We’d never heard of it. Later, we looked it up: une viande rare et un morceau méconnu, according to one description. It’s also called the araignée de porc: the pork spider.

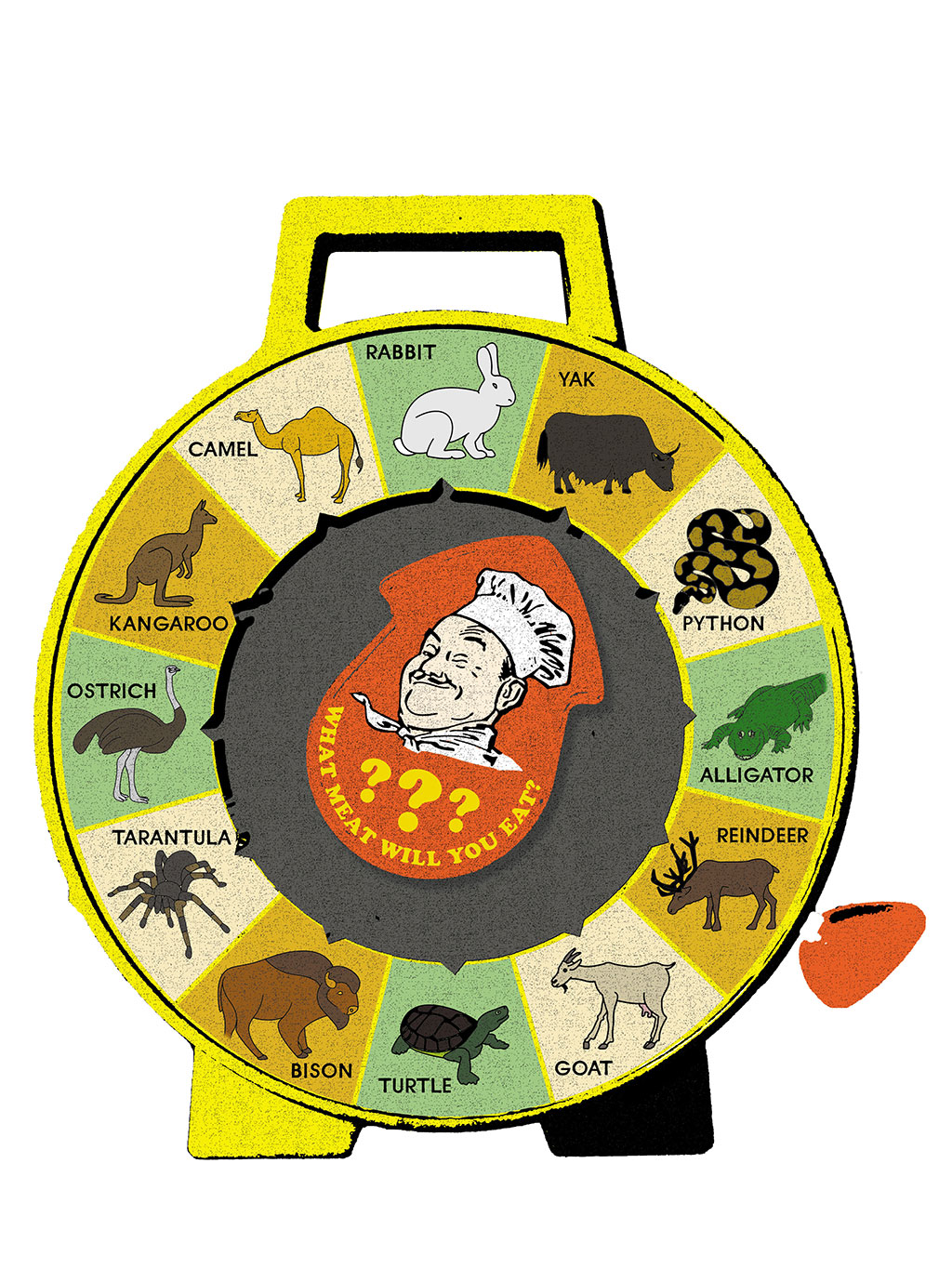

I thought of the pork spider when Bull City Burger and Brewery announced its annual Exotic Meat Month, with offerings including actual spider—tarantula, to be precise—and an ark’s worth of creatures from alligator to yak. As BCB&B puts it, this is “a chance to learn about new flavors and increase your cultural awareness. It’s also fun!”

Indeed—and it’s enriching off the palate, too. The world over, people eat animal proteins that Americans almost never do; they even prefer it. When I traveled in Cambodia, village markets offered deep-fried spiders and satay skewers of giant beetles as casually as if they were hot dogs; in the Laos dusk, kids waved spears in the air hoping to catch bats for dinner. But one needn’t go so far to find culinary exotica. The meat departments of many Latino groceries in these parts stock more organ meats than are dreamt of in your gastronomy.

For all the foodie-forwardness of the last generation or so, the American diet remains carnivorously narrow. Fun as it is to take the Survivor-ish challenge of tucking into, say, turtle (which is common in many other foodways, including our American South’s), there’s a real seriousness to this matter, and part of it is that we ritually exoticize even the most ordinary meats.

I asked Justin Meddis, who runs Rose’s Noodles, Dumplings & Sweets with his wife, Katie, what he knew about the cigalline. He’s a meat expert—Rose’s was a butcher shop before it transformed into a noodle-and-dumpling house—but he had never pursued the cut. It’s not easy to get at, deep in the animal’s hip.

Meddis considered and said, “I’m pretty sure that’s the muscle the pig shits with.”

Fear of feces, fat, funk. Apart from a few curious exceptions—what’s an oyster, after all, if not a salty, scatty, seminal loogy we’d flush down the toilet if it were ours?—we like our meat as de-animalized as possible: squarish, lean slabs of muscle. Meddis doesn’t broadcast that he still buys whole pigs from Firsthand Foods and uses almost everything but the squeal; but the tasty and rich little morsels of meat in his dumplings and soups answer to no supermarket name, and they’re perfectly counterpointed by the sweet-hot-acid qualities of so many non-Western sauces and condiments. Pigskin and lard contribute soul-filling viscosity and aroma to Rose’s ramen broth, and the pho broth utilizes otherwise neglected beef rib bones and hoof; Meddis freezes the latter afterward and, when he has enough in store, makes tendon salad.

Deft and ingenious use of “exotic” meats or neglected parts is one thing; deliberately eating them “kind of depends on your upbringing,” Meddis says. Consider shad roe, whose short annual season is underway right now. This long-celebrated delicacy has lost most of its currency in our increasingly monocultural foodways. But it persists at Locals Seafood, the estimable Raleigh-based wholesaler/retailer—now with a new oyster bar in Raleigh’s Transfer Company Food Hall—that stays true to its mission to purvey North Carolina seafood in all its variety. Rose’s sources the bluefish and mullet currently on its menu from Locals.

“All this tasty fish is being caught on our coast,” says Locals cofounder Lin Peterson. Much of it is by-catch, and that’s where both flavor and value swim. The bland white grouper and red snapper are in such high demand, and thus so heavily regulated, that Locals has to charge well over $20 per pound for them. Yet they offer numerous alternatives, often for half the price and with cooler names: blueline and golden tilefish, jolthead porgy, and sheepshead, which was once so popular that a New York City bay bears its name. Locals has helped create a lively market for previously ignored species like jack, a steaky fish that provides a cheaper, more flavorful alternative to mahi-mahi (which, Peterson notes, was once considered little better than a trash fish itself). Ditto the sweet, meaty triggerfish, which has also ascended to the upper ranks.

Still, even triggerfish poses secondary challenges. It yields a very low proportion of filet: Only about a third of its weight. But there’s much more meat on its bones, especially up around the collar where—as any lover of sushi-bar hamachi kama can tell you—some of the most flavorful meat is. Locals offers whole triggerfish, dressed and prepped for grilling or roasting.

Eating as much of the animal as possible is a better way to feed the world. It’s a way to take better care of it, too. Studies have shown that raising livestock is one of humankind’s most environmentally damaging (not to mention inhumane) industries; it’s more damaging still when we discard most of the beasts we breed or catch. And overfishing the most popular seafood species is causing endangerment and ecological crises. Carcasses do find their way into pet food, fertilizer, and other secondary uses, but an alarming portion of restaurant-bound animals end up in dumpsters.

Meddis points from Rose’s toward Brightleaf Square. “There’s a restaurant over there that wheels three carts a day past us to their garbage station,” he says. “We fill two small cans of trash a week.”

“Exotic” meat, whether pork spider or actual spider, is a way to broaden not just our dining horizons, but ourselves, gastronomically, economically, and culturally. “Eat things you’re not used to,” Peterson says. “We’ve got to get away from the skinless, boneless world. It’s not like we’re selling eyeballs.” Not yet, anyway.

food@indyweek.com