Illustration by Steve Oliva

In 1836, the estate of Edenton planter John Blount was donated to the two-year-old Wake Forest College, with the proceeds designated to support “poor and indigent young men destined for the ministry.” The bequest included land and, when Blount’s widow died in 1859, fourteen enslaved people who were auctioned for $10,718, the equivalent of about $330,000 today.

For the first 128 years of its existence, this institution—whose endowment was financed in part by black bodies—excluded black students. And when Wake Forest University finally admitted a black student in 1962, he was Ghanaian, not African American.

The university’s troubled history with race burst into the open in February—the same time Virginia governor Ralph Northam faced a scandal over appearing in blackface in the eighties—with the revelation that the university’s dean of admissions and an assistant dean of admissions had posed with the Confederate flag as students in the 1980s. During one of two public apologies, dean of admissions Martha Allman said she didn’t think that much about what the flag signified in 1982, when she took part in a group photo as the “sweetheart” of the Kappa Alpha Order fraternity. (She was engaged to a member.)

“I was not politically active,” Allman told administrators and faculty in April. “I was not engaged in discussions about diversity, nor involved in issues of social justice. In retrospect, I’m ashamed of that lack of awareness, but it’s true. I read applications and I meet new students, and I’m aware that there are a lot of students who become aware in their youth, and for others it just takes longer.”

Many of Wake Forest’s black students, who comprise 9.4 percent of the student body, say there’s never a time on campus when they can avoid thinking about race.

“It seems like my blackness is something that other people need to figure out how to navigate in academic and social settings,” says Kate Pearson, a rising sophomore. “My blackness is something I have to wear on my sleeve, which is exhausting.”

Wake Forest is part of a troika of elite universities in North Carolina, alongside the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and Duke University, that have outsize influence in state politics, business, medicine, and law. They’re renowned research institutions that feed hospital systems and influence cultural discourse through highly regarded faculty. The three have produced U.S. presidents, senators, governors, and judges: Richard Burr and Jesse Helms (Wake Forest); Governor Cooper, former governor Jim Hunt, U.S. Representatives David Price and Virginia Foxx (UNC); former president Nixon and Trump policy adviser Stephen Miller (Duke), among others.

In particular, UNC-Chapel Hill—mythologized as a “light on the hill”—has held a reputation as an engine of progress in North Carolina. As former governor Terry Sanford observed in a 1990 interview, most of the state’s leaders had come from Chapel Hill, which “had that concept of how to make the world better as a function of the university.”

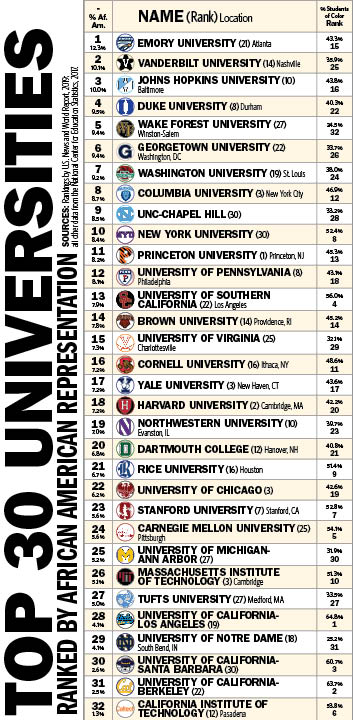

Compared to the nation’s other top-ranked universities, these are relatively diverse institutions. Among U.S. News and World Report’s Top 30 Universities in the U.S. in 2019, Duke has the fourth-highest percentage of African American students, Wake Forest has the fifth, and UNC-Chapel Hill has the ninth—the highest ranking among public universities in that elite group.

But these are still predominantly white institutions. At each school, as of 2017, black students comprised less than 10 percent of the student body, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, though they accounted for more than 21 percent of the state’s population.

For many black students, enrollment at these schools offers access to resources they wouldn’t have at historically black colleges, but comes at a steep psychological cost.

Growing up in North Carolina, Jerry J. Wilson watched his two eldest sisters attend mostly white schools in the UNC system, only to drop out. Another set of sisters attended HBCUs and graduated.

“When it was my turn, I got a strong nudge from my parents to consider an HBCU,” Wilson says.

He chose Fayetteville State University, which offered him the best financial aid package. Wilson is now a doctoral student at UNC-Chapel Hill’s School of Education.

“When I got here to Carolina, things were very different from Fayetteville State: programs, scholarships, study abroad, and facilities,” Wilson says. “So much, so many more resources than I had access to at Fayetteville State. I remember being in awe, like, wow.

“That’s why I go back to this notion of democratic equality, what it means for the flagship institutions to have all these resources, yet have this disparity when it comes to enrollment by race,” he continues. “Because the reality is it’s not just what you know, it’s also who you know, and what type of resources you have access to. It is the case that students at other universities may be receiving a wonderful education, but how well they’re able to take advantage of their opportunities is outside of their control. In terms of opportunities for research, we have Nobel laureates on the faculty at Chapel Hill. That means something for young people who are applying for other opportunities and are interested in a certain topic or need an introduction or a research apprenticeship.”

Aries Powell attended mostly white K-12 schools in Delaware but wasn’t prepared for the intensity of whiteness at Wake Forest.

“It’s pervasive, in-your-face violent whiteness,” says Powell, who uses gender-neutral pronouns. “Wealthy, elite whiteness. I’m solidly middle class. I’d always gone to school with people making similar amounts of money. I had a lab partner, and he was like, ‘I’m going to drop out.’ I’m like, ‘What?’ He said, ‘It’s no problem. My dad owns a potato chip company. I’ll just go work for him.’”

While Powell describes Wake Forest as an “adversarial place” academically and socially, they, too, acknowledge several advantages: They received a full-ride scholarship, ducking $200,000 of debt. The university paid for two study-abroad experiences, sending Powell to Cuba and Ghana. And undergrads with the requisite GPA or LSAT scores are automatically admitted into Wake Law.

While UNC-Chapel Hill is a public university and Wake Forest is not, their histories of race track closely together.

At UNC-Chapel Hill, slavery also played a clear role in establishing the university: Enslaved persons literally built the facilities.

The first public university in the United States, UNC-Chapel Hill—which was chartered in 1789 and opened in 1795—excluded black people for the first 156 years of its existence. And then it integrated only because it had to.

In 1951, a federal court ordered the university to admit five black graduate students under the “separate but equal doctrine,” because the state didn’t adequately fund medical and law programs at black institutions. Four years later, UNC-Chapel Hill admitted three black students, all graduates of Durham’s Hillside High School, to comply with Brown v. Board of Education. Five years later, in 1960, there were still only four black freshmen.

UNC’s website tells a flattering version of what happened next. While there were just 113 black students in 1968, “after a major recruitment initiative, 138 professional and 946 undergraduate students were enrolled in 1978. The university has become a national leader in this area.”

Like other prestigious schools, UNC-Chapel Hill has made public commitments to increasing diversity over the years. In 2000, for example, the Minority Affairs Review Committee declared this goal “a fundamental prerequisite to both educational excellence and the university’s ability to serve all the people of the state.”

However, black enrollment at UNC-Chapel Hill actually plateaued in the late nineties, then began to drop in 2010, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. UNC spokeswoman Kate Luck says changes in federal reporting guidelines account for a 1.5 percentage point decline between 2009 and 2010. Even so, the percentage of black students at UNC-Chapel Hill fell to 8.5 percent by 2017.

Similarly, N.C. State—the state’s largest public university, with more than thirty-three thousand students—saw black enrollment top out at 10.4 percent in 2000 and fall to 7.2 percent by 2017.

Duke University, founded in 1838, didn’t admit a black graduate student until 1961 and black undergrads until 1963. Black enrollment at Duke increased from 6.5 percent in 1990 to 10.6 percent in 2004, fell to 8.3 percent in 2010, and rebounded to 9.5 percent in 2017.

In the late seventies, as public institutions like UNC-Chapel Hill were making strides in increasing black enrollment, Wake Forest found itself under pressure to become more diverse. Herman Eure, one of the university’s first two tenure-track black faculty members, created the Office of Minority Affairs in 1978.

Martha Allman was a freshman that year. After graduating in 1982, Allman went to work as an admissions counselor at her alma mater, then became the undergraduate admissions director in 2001. In that role, in 2008, she instituted test-optional admissions to reduce barriers for black and brown students, making Wake Forest the first Top 30 university to do so.

Under her leadership, the share of students of color in Wake’s undergraduate programs has risen from 14.8 percent in 2007 to 22.9 percent in 2017.

During her second public apology for posing with a Confederate flag in college, Allman boasted that “Wake Forest’s nonwhite student population has now grown to over thirty percent.” University spokeswoman Katie Neal says Allman’s figure accounts for international students.

But the share of black undergrads has barely budged—from 6.8 percent in 1990 to 7.5 percent in 2017, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Higher numbers of students of color in graduate programs push African-American representation across all levels up to 9.4 percent, still well below African Americans’ 35 percent share of the population of Winston-Salem.

Nate French, who heads Wake Forest’s Magnolia Scholars program to support first-generation students, says the reason for African Americans’ under-representation is straightforward: “It’s a poor K-12 preparation program. We can’t recruit students if they’re not prepared to come out of high school. I think the report last year in Winston-Salem is that only twenty-seven percent of African Americans hit third-grade proficiency. That number’s not going to go up exponentially by the time they get to twelfth grade.”

Meanwhile, high-achieving students of color—or, for that matter, low-income or rural students—are highly sought-after by higher-profile recruiters.

“I think all the schools—and I’ve been out on the road recruiting for Wake—you’re trying to beat the bushes to find students,” French says. “But if you find one or two or three—and this is red or yellow, black or white—if you find the kid that can get into Wake, they can get into Carolina, they can get into State. Everybody’s going for that student, so there’s a lot of competition there.”

During their first year at Wake Forest, Aries Powell took part in a historic simulation set in Greenwich Village in the 1910s and ’20s. The story was about labor, says Powell, but the class’s white students shifted the narrative to class—and Powell was the only African American among them. Powell used the word “Negro,” wanting to be historically accurate, a decision they quickly regretted as their counterparts began using the word with relish.

“The white students ran wild with it,” recalls Powell, who graduated May 20. “I said, ‘Can we stop? This is a little much.’ The professor made me plead my case, and then put it to a vote.”

Beyond the everyday racism that Powell experienced, more overt and outrageous examples are legion at Wake Forest.

Among those that have made the news in the last five years: A bucket of urine was placed outside a black Muslim chaplain’s office. A white fraternity invited guests to dress like performers in a rap video. The night of Donald Trump’s election, white students ran around campus yelling the N-word. A white student called her black resident adviser the N-word. A student’s Instagram post called for a wall separating Wake Forest from the HBCU Winston-Salem State University.

“Everyone in your classes could be incredibly racist,” Powell says. “Your roommate could be incredibly racist. The thing that’s so hard is the consistency.”

Asked what Wake Forest is doing to combat racism on campus, vice president for diversity and inclusion José Villalba points to a workshop that includes discussions on “multicultural competence” and “micro-aggressions” that all first-year students are required to attend.

Like Wake Forest, Duke University has had its own episodes of racial tension. Last year, vice president Larry Moneta made news after his complaints about rap music at an on-campus coffee shop got two baristas fired. Earlier this year, Megan Neely, a graduate director in the university’s medical school, stepped down following a backlash that emerged over an email she wrote admonishing Chinese students to speak English “100% of the time.” And in 2014, executive vice president Tallman Trask III allegedly called a black parking attendant a “dumb, dumb, stupid [N-word]” after striking her with his Porsche, leading to days of student protests in 2016, after a lawsuit brought the incident to light.

Gary Bennett, Duke’s vice provost for education, told the INDY in a statement that the university is “constantly working to cultivate a climate in which free expression is encouraged, and one that is characterized by mutual respect, appreciation for difference, and inclusivity.”

For Jerry J. Wilson, being one of the few black grad students at UNC-Chapel Hill often means feeling that his academic interests are devalued.

“For us in the school of education—for me and the other students of color—it’s trying to find scholarship with which we identify,” he says. “A lot of us prefer more critical work, work that challenges dominant narratives, work that aims to transform oppressive systems. There are few faculty in the school of education that take that approach.”

He’s not alone. In November, under pressure from students—including Wilson—the university published a two-year-old survey in which nearly two-thirds of black or African American students and staff said that they felt “isolated in class because of the absence or low representation of people like me,” The Daily Tar Heel reported.

As evidence of UNC-Chapel Hill’s progress in increasing “underrepresented minority enrollment,” spokeswoman Kate Luck says that 8.6 percent of first-year students at UNC-Chapel Hill identify as African American, the highest percentage among U.S. News and World Report’s top twenty-five public universities.

But if you include all undergraduate and graduate students, three of those top public universities—the University of Maryland, Rutgers University, and the University of Georgia—have a higher representation of black students than UNC-Chapel Hill’s 8.5 percent, according to an analysis of National Center for Education Statistics data.

Even Carolina’s level of diversity is under assault from those who consider it affirmative action.

A group called Students for Fair Admissions sued the university in 2014, claiming that the UNC’s consideration of race in admissions “equates to a penalty imposed upon white and Asian-American applicants.” The group has filed similar lawsuits against Harvard University and the University of Texas at Austin, which are expected to go to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In February, members of the Wake Forest’s Anti-Racism Coalition took over a forum on inclusivity hosted by Villalba. But while they called attention to Allman’s picture with the Confederate flag, their concerns and demands went further. They demanded a dedicated space for the Black Student Alliance, a “zero-tolerance policy” for acts of white supremacy, transparency in the bias-reporting process, additional black counselors to support black students, and the removal of monuments and building names that commemorate Confederates and eugenicists.

In addition to the Allman’s two apologies, the administration responded by designating a lounge at Kitchin Hall for the Black Student Alliance.

“We had to literally shut shit down to get that,” Powell says. “We had to make this administration afraid of us. This campus does not cater to or care about black students.”

The university has also pledged to review its bias-reporting system, and President Nathan O. Hatch announced that a commission on race, equity, and community will convene in September.

Black student activists at Wake Forest say that increasing diversity isn’t their top priority. There’s too much bigotry to ask new black students to join them.

“The [black enrollment] stat is depressing and disgusting, but the fewer students of color, the better, as a matter of harm reduction,” Powell says. “This campus has the potential to be a great place for black students. We are at the beginning of a long path. We are a long way from black students being safe and OK here. I don’t want to tell black students to be here to enlist them in my war. I understood that I was taking on this work when I came here.”

Meanwhile, at UNC-Chapel Hill—which, unlike Duke and Wake Forest, often finds itself at the mercy of state politicians—black students and faculty are pushing forward amid uncertainty over the future of Silent Sam, with the UNC Board of Governors’ recent announcement that a decision over the fate of the Confederate monument will be delayed indefinitely.

“We spent half a million dollars protecting a Confederate monument,” says William Sturkey, an assistant professor of history at UNC-Chapel Hill. “We do not have a historian of slavery at Carolina. One of the messages that conveys is that several hundred people who volunteered to fight for North Carolina when it left the United States are more important than the thousands of people who were slaves who were connected to the university, hereby privileging one race over another. That’s a choice we make in 2019.”

A version of this story originally appeared in Triad City Beat. Disclosure: The author was employed by Wake Forest University in fall 2017 to lead an independent study. Comment on this story at backtalk@indyweek.com.

Support independent local journalism. Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle.

What I would like to know is the number of blacks applying to these universities compared to the number of whites and the numbers accepted and rejected. Also, what are their academic accomplishments? What were the high school GPAs and SAT scores of those accepted and rejected? Going by the premise that NC universities and all white people are inherently racist, maybe the answer is to ban all white people from public universities and tax whites only to pay for the education of non-whites? Would that make the leftists happy? To judge people by the color of their skin, their character be damned? Please, somebody tell me what the solution to this is. If the problem is white people, I guess the only answer is to get rid of white people. That is the only conclusion all of this race baiting bullshit ever implies.