TORRY BEND & HOWARD L. CRAFT: DREAMING

Friday, Nov. 22–Sunday, Nov. 24

8 p.m. Fri. & Sat./7 p.m. Sun., $25

Von der Heyden Studio Theater, Durham

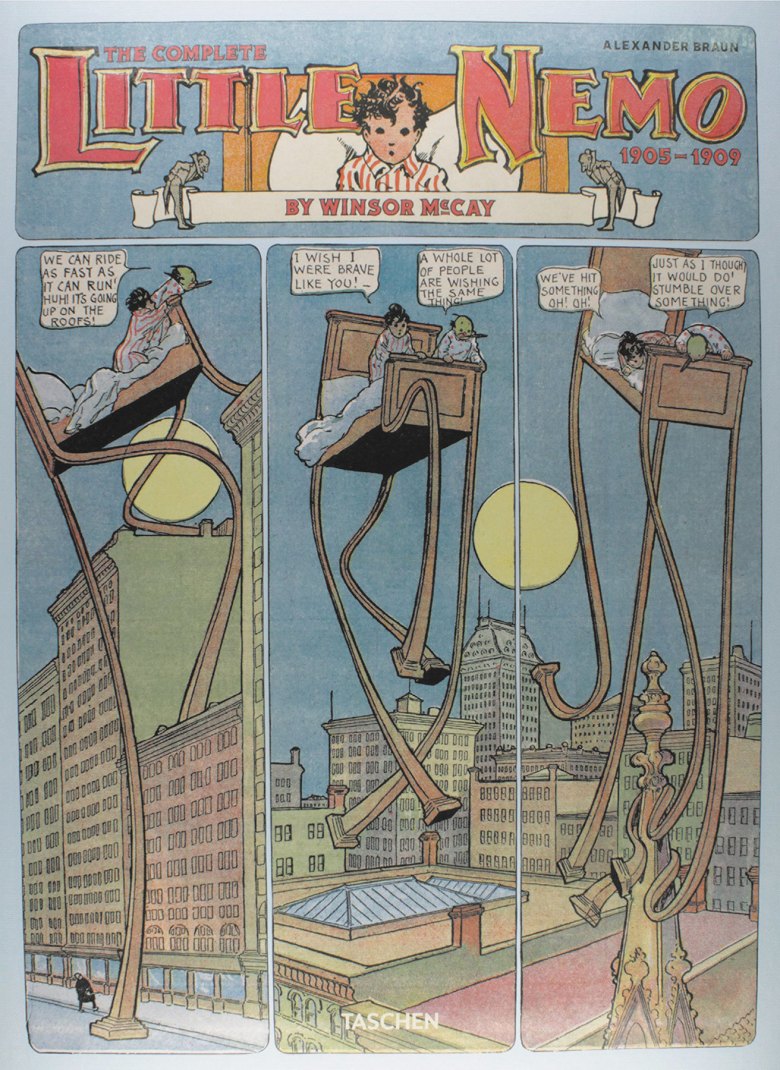

It’s evident that Little Nemo in Slumberland is beautiful. Winsor McCay’s Art Nouveau-influenced illustrations are at once whimsical and precise, elegant and magical, as he serializes a little boy’s nightly adventures in a fantastical dreamland.

It’s evident, too, that Little Nemo is important. McCay’s early-twentieth-century innovations in perspective, scale, pacing, color, panel structure, and other core aspects of cartooning—to say nothing of his later inventions in the young field of animation—helped to create the template upon which future greats, from Hal Foster and Robert Crumb to Walt Disney, would iterate.

It’s also evident that Little Nemo is problematic, and this is where Torry Bend and Howard L. Craft enter the picture.

Bend, who lives in Durham, is a puppet-theater artist who has delighted audiences from the Bull City to New York: Duke Performances previously commissioned Love’s Infrastructure, her collaboration with the band Bombadil, and The New York Times called The Paper Hat Game “an unexpected mitzvah.”

Craft is the Durham-based playwright who created both the African-American superhero radio serial Jade City Chronicles and Freight: The Five Incarnations of Abel Green, which the Times called “rich and thoughtful” and the INDY gave five stars.

Dreaming, their new puppet-theater take on Little Nemo—which premieres at The Ruby via Duke Performances this weekend—aims to give the ethnically varied sidekicks who surround the Waspy Nemo what McCay never did: a voice and a choice.

For the first quarter of the twentieth century, McCay’s full-page strip reached a national audience in major New York papers, and it brought that readership recurring characters such as Impie, an African “jungle imp” drawn with all the outrageous caricatures of the time. Impie, who speaks gibberish, was stolen from Candy Island by Nemo’s green-faced nemesis, Flip, a drunk-Irishman stereotype.

Bend didn’t really notice these characters upon first encounter, years ago, when her mother gave her a Little Nemo book she found at a garage sale. Based on her fond but fuzzy impressions of it, Bend decided to adapt it for Manbites Dog Theater’s final season. It was in the public domain, and the presentiment of animation in McCay’s dynamic drawings made it perfect for puppet theater.

Only when Bend dug into the material did she discover the toxicity she’d missed for all the wonder. She almost dropped the project.

“It was around the same time that the Charlottesville incidents were happening, and I started to become very nervous about what it means to remake work from historically influential white men without really interrogating the darker sides of them,” Bend says, sitting with Craft outside the Ruby’s von der Heyden Studio Theater, where a group of young people are busy painting and cutting puppets.

In looking at many other modern adaptations of Little Nemo—movies, plays, and comics—Bend was shocked to find that many of them either omitted Impie, or worse, uncritically perpetuated the character. She cancelled the Manbites show, but she also reached out to Craft to see if he wanted to write a Little Nemo-based play that she could adapt, instead.

“It felt like exactly the kind of thing Howard had been doing: the performance of Black bodies, the history of blackface in Abel Green,” Bend says.

Craft is a comics fan, but his tastes run more to Marvel and DC superheroes than classic newspaper strips. Still, he says he quickly realized that puppet theater was less like writing a play than like writing a graphic novel—more show than tell. He had never encountered McCay’s work before, but he immediately perceived its influence, for good and for ill.

“His use of color and space was really interesting. But [his depictions] are like a backlash against Reconstruction,” Craft says, mentioning how many Confederate monuments were built in the same period. He remembers encountering images similar to Impie’s in Looney Tunes and Tom and Jerry cartoons as a child. “That dehumanizes, makes it easier to kill a person or discriminate against a person. It’s like with the Washington Redskins—you can’t dismiss that, where your nostalgia is more valuable than someone else’s humanity.”

To try to draw out that context without forsaking the magic that makes McCay’s work worth remembering at all, Craft came up with a compelling device: The characters are auditioning for their roles in Little Nemo, like actors, but to get the work, they have to submit to McCay’s vision and relinquish their humanity. Different characters make different choices, but all tug on complex contemporary issues of opportunity and representation.

“McCay had the freedom to depict races of people however he wanted to, but the people he depicted weren’t free of the repercussions of his depictions,” Craft says. “I’m imagining, what if they had a say? What choices would they make, and how would it play out based on their social context? There are very real choices African-American artists have to make: If Tom Hanks plays a Dumb and Dumber type role, it’s just Tom Hanks playing a role, but if Denzel Washington does it, it’s a comment on Black America. Oftentimes, the choice is between eating as an artist and not doing the art.”

In dealing with the unexamined racism of McCay and his son, Robert, Craft didn’t want to write a polemic, both because he’s a better storyteller than that and because to do so would let contemporary audiences off the hook too easily. After all, when we encounter monsters, our usual takeaway is just relief that we’re not monsters.

“Klansmen got children, grandmas, they might be sweet to their families on Thanksgiving,” Craft says. “Most racist people don’t think they’re racist. When you present these people as uncomplicated, you allow people who may have similar feelings but keep them to themselves to say, that guy’s a racist, and I’m not. But if you show a complete human, they can see themselves and people in their family. If we did it the other way, we’d be doing the same thing Winsor did, making a caricature.”

Dreaming, which already has a New York premiere slated for a puppet festival at La MaMa in November 2020, consists of three kinds of puppetry, with the puppeteers visible on stage. There’s shadow puppetry on overhead projectors. There’s toy theater, with flat, jointed puppets that are about sixteen inches high. And there are dimensional tabletop puppets in the Japanese bunraku style, with multiple puppeteers working the hands and feet.

This format not only allows the material to exist in shifting, dreamlike layers, it also allows the characters to change, which is crucial in a show about self-representation. With the staging primed to capture all the surface wonder of McCay’s comics and the material geared toward processing its inner problems, Dreaming seeks the seam where nostalgia stops and cultural violence begins, which perhaps puppetry can uniquely do.

“Puppetry is an interesting medium for having conversations about representation and embodiment,” Bend says. “You are giving life to another life-form in this very literal way. As soon as you have multiple bodies performing a character, it then also becomes this community effort to give life.”

bhowe@indyweek.com